The Importance of Art Education with or without AI

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman argued that modernity is characterized by fluidity and that “the job of critical thought is to bring into the light the many obstacles piled on the road to emancipation.” (Bauman, 2000, p. 51).

The social and political discourse around AI in art and AI in education is nothing new. For centuries humans have been blindsided by technologies that caused structural rupture and shifted entire societies. Often associated with late capitalism specifically (Mandel, 1975), structural crisis broadly defined occurs when predominant social norms and customs are forced into widespread change. Anthropologically, when humans settled into agricultural communities or when the steam engine spurred the Industrial Revolution, ways of life, cultures and traditions shifted alongside the developments in production.

Mass media has a long and varied history, and there are touch points that illustrate the structural shifts that have led to the world we live in today. The release of AI tools for mass consumption may be one of these touch points, but it is not a force that is changing what education is nor what an education should entail. AI is created and bankrolled by billionaires and fund managers who explicitly threaten our emancipation – these are the forces working to change what education means and who has access to it.

We face multiple, interconnected crises – climate change, economic inequality, social fragmentation – and these crises are shaping the conditions for education. AI may be one technological response, but it is not a panacea. AI’s predominant data collection model reflects an extractive system that prioritizes efficiency and production over social justice and equity – a trend that deepens existing inequalities. The issue of power plays heavily into the development, deployment and use of AI tools and systems.

AI in Art Education

Educators and artists have historically been people who help us to break outside of the hype of technological advancement, helping us to understand its implications, showing us what challenges to power can look like and encouraging us to return our focus to human development and connection. They are the people who work to ensure inclusivity and extend the fundamental belief in education as a basic human right.

While AI may be a worthwhile tool for creative expression, art education continues to be a human rights issue as “Culture and the arts are essential components of a comprehensive education leading to the full development of the individual.” (UNESCO, 2006). AI can allow an artist to reimagine their expression, but the initial neurological relationships and concepts are what make art, art. This was always an underlying lesson in Art Education, an endeavour which includes an attempt to understand the unique neurological connections that help a person explain complex feelings and connections.

“[the] emphasis on the development of cognitive skills, to the detriment of the emotional sphere, is a factor in the decline in moral behaviour in modern society…Without an emotional involvement, any action, idea or decision would be based purely on rational terms…Arts Education, by encouraging emotional development, can bring about a better balance between cognitive and emotional development and thereby contribute to supporting a culture of peace.” (UNESCO, 2006).

Artists have long employed themselves or been employed to process social emotional positions and to imagine futures. Russian artists Kasimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky were artists who believed that art was a spiritual venture, while they had contemporaries, like Alexander Rodchenko, who rejected “art for art’s sake” and insisted that art was political. (Meggs, 2006). Russian Suprematism and Constructivism explored the relationships between art and power early in the twentieth century. Indeed a related art movement directly after the Russian Revolution in 1917, Productivism, sought to image a utopian future. The Russian avant-garde artists embedded themselves firmly in society designing festivals and concerts, and participating in civic society to imagine the future. (Gardner, 2005).

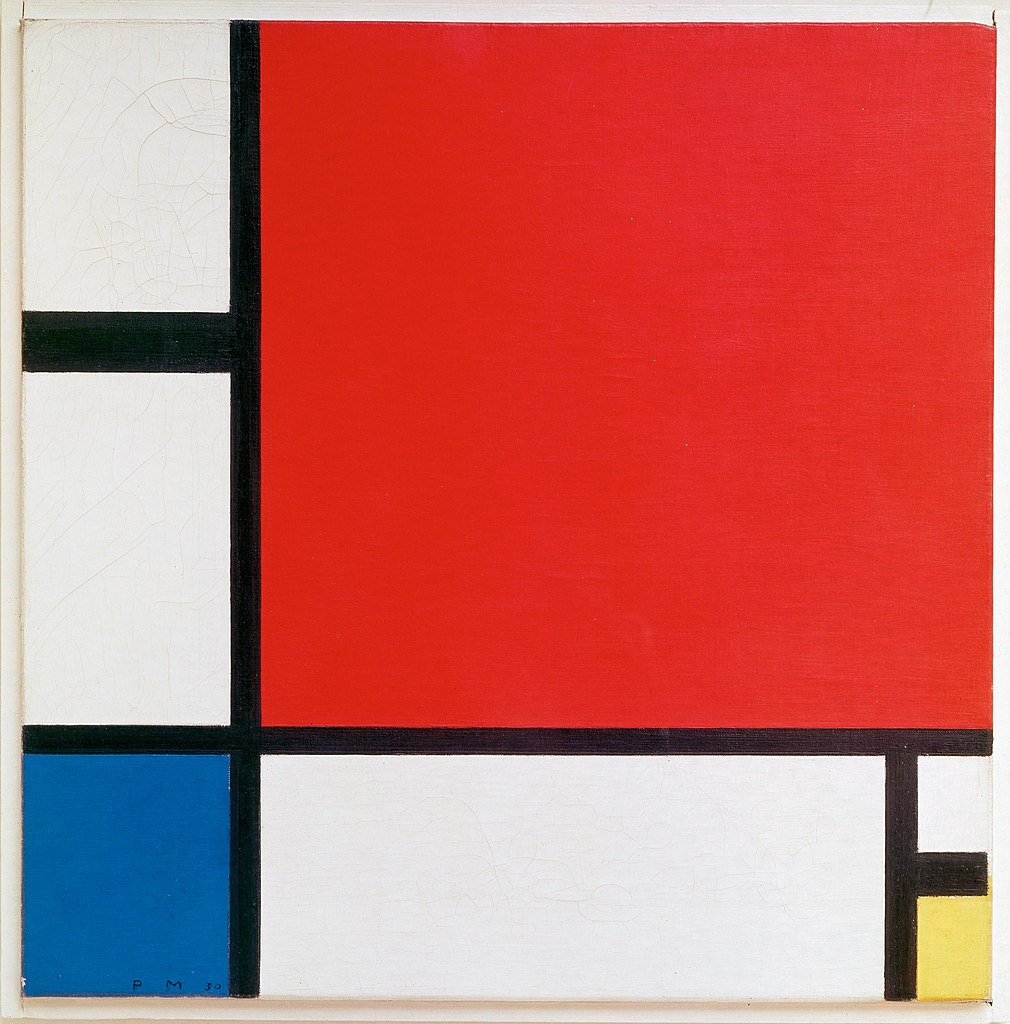

De Stijl, an artistic movement around the same time in Holland, had members who also explored utopian ideals, writing and making art that sought to transition from individual “consciousness” to a collective one. Bauhaus taught artists, architects and designers how to build for society and anticipate the needs of the 20th century.(Gardner, 2005).

During the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, black artists like Nina Simone and Jean-Michel Basquiat used art as a tool for cultural affirmation and resistance against systemic oppression. Indigenous artists use traditional crafts, performance art, and digital media to assert their cultural identity, document their struggles, and advocate for environmental protection. Punk Rock artists used lyrics and aesthetics to challenge social norms, criticize political corruption, and promote DIY culture.

Indeed, it is recognising, processing and articulating feelings that likely leads to behavioural change (Burtynsky, 2022), and it is the purpose of art to interweave this lesson as a tactic in progressive change.

AI and the Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) “provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.” Big Tech, multi-billion dollar companies insist that it is AI that will put us on a path to progress on global problems (Hilliger & Belshaw, 2025), yet they are actively working against each and every one of the SDGs.

The pursuit of individualised data and learning through AI risks further deterioration of social bonds and emotional development, and can reinforce existing inequalities. This undermines the SDG goal of “equitable access to quality education for all”. We must look at the issue of AI in education from the perspective of the socio-political and economic systems within which we live. A proactive educational position on any form of AI uses critical analysis to understand the context within which a particular AI tool has been developed and trained. Such a position will also take into account the associations between the SDGs and the AI tools we use.

In the call for think pieces on AI and the Future of Education, UNESCO’s IdeasLAB wrote that AI “technology is forcing educational institutions across the world to reconsider what knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours are most important for life and work.” This piece argues that they shouldn’t be, rather it is the technology, if anything, that should be reconsidered. The history of the SDGs details the values with which we, as a global community, agree upon. The knowledge, skills and behaviours important for displaying and working on those values remain abstracted from the “technical skills” associated with technology in general.

Education is a process that comes from ambiguity and uncertainty. Art-making is a process much the same, filled with ambiguities and uncertainties. Wolfgang Klafki, a German educational theorist, wrote that there are three central tenets to being educated (Klafki, 1993):

- Self-determination: the ability to decide one’s own relationships and meanings in the interpersonal, professional, ethical, and religious spheres.

- Participation: the ability to participate in societal-political relations and take responsibility for that participation.

- Solidarity: the understanding that the claim to self-determination and participation is only justifiable if efforts are made to represent the rights of those who lack these rights.

There has always been nuance about the purpose of education. While Klafki believed in the tenets above, Martin Luther King, Junior thought that “the function of education…is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.” (King, 1947).

Educated use of AI therefore requires a “human in the loop” because Large Language Models (LLMs) are unable to self-determine, participate without human intervention, or show solidarity to others. AI may be gifted with reason, but it has no morals as moral philosophy and thought requires the ability to think. AI may infer, or be programmed to, establish positions from other thoughts, but the ability to string together into new and interesting ideas and information remains uniquely human.

As we have not solved our global problems and doing so requires new and interesting innovations and approaches towards the SDGs, we cannot rely on AI, now or in the future, to find the solutions for us.

AI as a Fascist Aesthetic

Art has often been a visceral rejection of mainstream values and a call for radical change. Artists recognised that art exists within a contextual and cultural space, as does technology. Walter Benjamin wrote that “mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual…the instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice – politics.” (Benjamin, 1936).

AI has given us the ability to regurgitate and visualise techno-solutionist values without acknowledging the lack of consensus on those values. We live in a world of algorithmic radicalisation where a tiny minority insist that their ideas, values, skills and knowledge are authoritative. In short, a fascist, technologically deterministic moral philosophy. AI is a reflection of a “fascist aesthetic” – a system of imposed values.

Walter Benjamin also wrote that “[our own] self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”

Indeed, we know what many of the solutions to global problems are, but our social and political landscapes make it improbable to enact these solutions. It is the ethical responsibility of educators, policymakers, and technologists to ensure that AI is used in ways that promote social justice and sustainability, or, given the current societal context, not used at all.

As the conversation around AI becomes a steady drumbeat of insistence that it will, whether we want it to or not, change our entire social and cultural landscapes, educators and artists must remain firm on the true value of education and of art. In harmony with our collective goals for sustainable development, we must resist the temptation to completely redefine critical literacies through the lens of AI and remember that our human neurological connections and social contexts help us create equity, inclusion and justice.

Acknowledgements

This article was written and submitted as a response to a UNESCO call for think pieces. Thank you to Bryan Alexander, Helen Beetham, Doug Belshaw, Ian O’Byrne, and Karen Louise Smith for conversations that helped with the development of this article. Check out their responses to UNESCO’s call on AI and the Future of Education:

- Several Futures for AI and Education by Bryan Alexander

- How the right to education is undermined by AI by Helen Beetham

- Marching Backwards into the Future: AI’s Role in the Future of Education by Doug Belshaw

- Reimagining AI in Education: From Threat to Cognitive Amplifier by Ian O’Byrne

- Building warm expert expertise to mitigate against data harms in AI powered edtech by Karen Louise Smith

Footnotes

- El Lissitzky 1919 Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge The political piece shows the red wedge (a symbol of the Bolshevik Army) slashing through the “white” forces that were in power. The text dynamically floats around the image, reinforcing movement of the cause. A student of Malevich, Lissitsky was perhaps the most prolific Constructivist. His work transformed Supremacism into the political statements Constructivism became known for. He believed that the Russian Revolution would create a new world order in which technology, art, social engineering and communism would provide for society and its needs. ↩︎

- Piet Mondrian, 1930 Composition (Blue, Red, Yellow) The right angel in this work takes on great importance because the Mondrian’s philosophy is based on two ideas the platonic forms and yin-yang; underlined order, pure forms, this idea led to the development of “neoplasticism“, “pure plastic art”. Movement is observed because the lines don’t go all the way to the edges. He wanted to create dynamic equilibrium and dynamic harmony. He felt yin-yang was too soft. Pure geometry/ platonic clarity, colors have certain weight. It uses very simple means but there are variations to a particular idea such as reductive extraction, primary colors, squares, and lines. Mondrian lived his life how he painted, his apartment and belongings were completely geometric and he was obsessive compulsive. Mondrian believed nature is a fake copy of the true idea.

↩︎ - Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1982 Untitled This 16 foot wide painting features reference to Basquiat’s cultural and social heritage. As a painter, Basquiat often used symbols and textual elements to pay homage to various subcultures and social activities. This particular painting was created along with seven others when Basquiat was invited to do a show in Modena, Italy. The show was ultimately canceled, and the 8 paintings where separated until a gallery show at the Fondation Beyeler in 2023. Photo cc-by-sa Laura Hilliger ↩︎

References

- Benjamin, W. (1936) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Schocken/Random House, ed. by Hannah Arendt.

- CBC. (2022, June 10). Edward Burtynsky on the power artists have to inspire climate action. CBC Radio.https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whatonearth/edward-burtynsky-on-the-power-artists-have-to-inspire-climate-action-1.6484615

- Gardner, H., Kleiner, F. S., & Mamiya, C. J. (2005). Gardner’s art through the ages (12th ed). Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Hilliger, L., Belshaw, D. (2025). Harnessing AI for environmental justice Friends of the Earth. Retrieved April 23, 2025, from https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/reports/harnessing-ai-environmental-justice

- Klafki, W. (1993). Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik : zeitgemäße Allgemeinbildung und kritisch-konstruktive Didaktik. Weinheim [u.a.]: Beltz.

- “The purpose of education” | the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. (n.d.). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/purpose-education

- Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism (London: New Left Books, 1975).

- Meggs, P. B., & Purvis, A. W. (2006). Meggs’ history of graphic design (4. ed). Wiley.

- UNESCO. Road Map for Arts Education, 2006. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2022/12/Lisbon_Roadmap.pdf